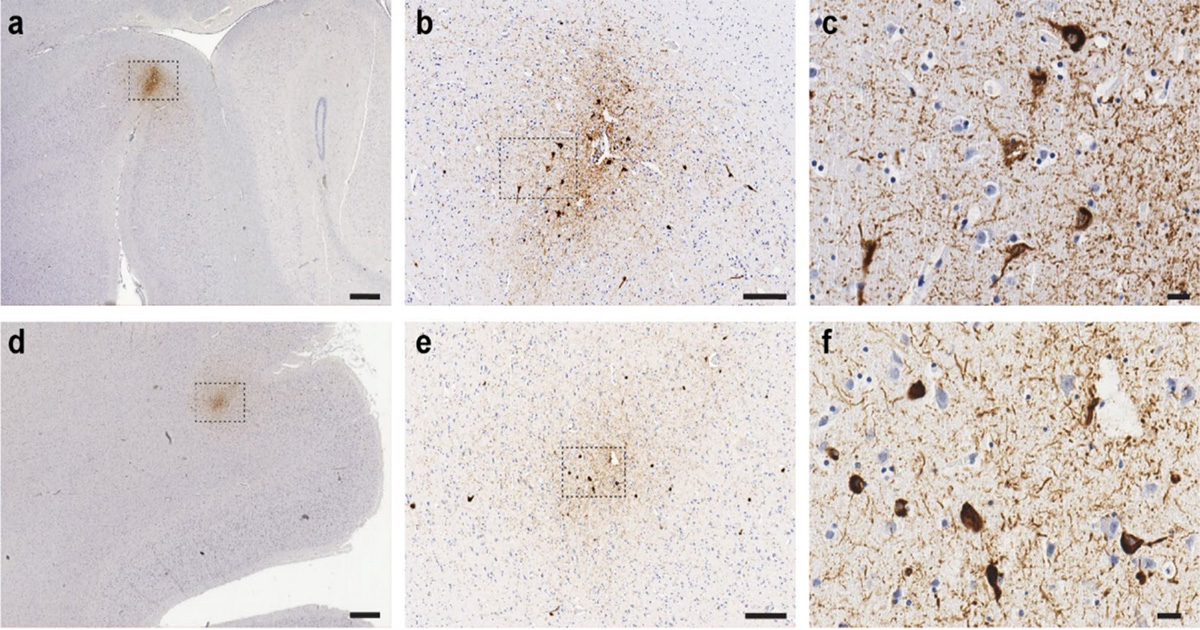

More sad but unsurprising news from the realm of football concussion, with reports that AFLW player Heather Anderson has been dubbed as the first female athlete to be diagnosed with CTE (Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy).

CTE is a brain disorder linked to repeated head injuries.

In a succinct definition by the Mayo Clinic, CTE gets worse over time, causing the death of nerve cells in the brain, known as degeneration.

The only way to definitively diagnosis CTE is after death during an autopsy of the brain, which is what happened in the case of Heather Anderson.

The former Adelaide Crows player was known for wearing a bright pink helmet during her eight games, but even with that attention to prevention, an exclusive ABC report notes that her injury-plagued career included at least one confirmed diagnosed concussion.

In my professional opinion, one concussion is too many.

Sadly, the on-going campaign that I’m part of, to prevent concussion in sports such as Australian Rules Football, soccer, rugby, and boxing (to name a few), continues to fall on deaf ears, eliciting token, post-hoc actions that are dodging the seriousness of the issue.

It should be game over for concussion in contact sports

Concussion can occur across the life span, happening to anyone at any time.

Humankind might be forgiven for developing contact sports in the past, but as our knowledge of the short and long term damage from head injuries has grown, the rules of yesterday need to change too.

In the wake of Heather Anderson’s story, the AFL has the opportunity to truly and finally take the high moral ground and immediately address the fact that players in its women and men teams are sustaining blows to their heads frequently during a game.

The rules of Aussie Football need to be reviewed and replaced immediately with new rules about the game of play and established statutory national policies. These changes cannot be left to the AFL alone. They have shown little appetite for change. It is mandatory an independent body comprised of medical experts, clinical and basic research scientists working in the field of sports related concussion, is established urgently to protect all AFL players, from the beginner to the elite, now and future generations.

Of course accidents will happen still, but dramatic rule changes that all but eradicate head and neck trauma as a normal part of play are outdated and show complete disregard for the “cash cows” of the league; the players.

And this will need to be addressed from the grassroots competitions, too, because no parents want to send their children to their death.

Indeed, as Professor Michael Buckland, Director of the Australian Sports Brain Bank, says, Heather Anderson’s diagnosis is a significant step in shining a light on the contact sport on women’s brains, adding to our insights about its effect on men’s brains.

CTE does not discriminate on grounds of gender

Early in the paper that is the source of reporting about the former Crows player, Professor Buckland notes how this case is worthy of serious attention throughout the AFL and other contact sport bodies.

Contact sports in which head injuries occur commonly (and also where CTE is most frequently reported) are historically male dominated, and this likely underlies the strong male bias in CTE prevalence to date. However, the last two decades have seen a rise in popularity and participation in women’s contact sports, particularly among younger women aged 15–34 years. Available evidence indicates that females are more susceptible to sports-related concussion than males, even when participation is controlled for. At present, there have been only a handful of CTE cases reported in females, and none have derived from professional athletes. Here, we report the frst case of CTE in a former professional female footballer.

Given that severe cases of CTE can present similarly to Alzheimer’s disease or depression, these symptoms don’t tend to appear until later in life.

What this means is that if the AFLW were to apply honesty to its recruitment drives, it should be painting a picture of what later life will look like for its players. Not a very attractive picture, at all, especially when, with some courageous rule changes, the risk of Alzheimer-like symptoms from head knocks during footy games could be all but eradicated.

Perhaps the telling blow comes from neuroscientist, Alan Pearce (who co-authored the report referenced above, Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in a female ex‑professional Australian rules footballer) who blames the lack of research into CTE on the limited support from major sporting codes.

As Alan Pearce told the ABC, “despite the fact that we know that women have greater rates of concussion, we haven’t actually got any long-term evidence until now. So this is a highly significant case study.”

Here’s hoping Heather Anderson’s legacy will be the catalyst to change that.

Until things change, the AFL will continue making money from the spectacle of its men’s and women’s competitions, leaving families and the healthcare system to pay the price for unnecessary head injuries and their long, long, long term impacts on individuals and those around them.

Image: The image is from the scientific paper, republished under Creative Commons 4.0: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.